The books we loved as children stick with us in a way that few contemporary best sellers and book club picks do. As we get older, we share these favorites with new generations just as they were shared with us, in the hopes that these treasured tales may ignite the same wonder and inspire a lifelong appreciation for books and reading. Some of these enduring stories have fascinating stories of their own behind them. A few seemed like duds when they were first published, while others were banned for promoting witchcraft or backtalk. One especially popular book was rejected by the New York Public Library for being too sentimental. But all have endured through the decades and are now widely adapted and awarded, included in numerous “best of” lists, and translated into countless languages. Here’s a closer look at just a few classic titles.

Goodnight Moon by Margaret Wise Brown

Margaret Wise Brown spent several years studying and working among teachers, researchers, and child psychologists at Bank Street’s Cooperative School for Student Teachers, a childhood development think tank and nursery school in New York City. There, she focused on language and semantics among the school’s young students, who favored sound and rhythm rather than actual communication in the early stages of education and socialization. It was this experience that informed Brown’s classic picture book Goodnight Moon — a story that is as much a soothing, rhythmic lullaby as it is a narrative yarn.

Margaret Wise Brown spent several years studying and working among teachers, researchers, and child psychologists at Bank Street’s Cooperative School for Student Teachers, a childhood development think tank and nursery school in New York City. There, she focused on language and semantics among the school’s young students, who favored sound and rhythm rather than actual communication in the early stages of education and socialization. It was this experience that informed Brown’s classic picture book Goodnight Moon — a story that is as much a soothing, rhythmic lullaby as it is a narrative yarn.

The book came out in 1947, when most other books for children were retellings of fairy-tales and fables. The fact that Goodnight Moon was a new story with a contemporary setting was almost revolutionary; it represented the “here-and-now” philosophy popularized by Bank Street and its founder, Lucy Sprague Mitchell. The story follows the bedtime ritual of a bunny who says goodnight to various objects — the moon, a red balloon, a little toy house, a little white mouse — before finally drifting off to sleep. Clement Hurd did the illustrations, which are full of Easter eggs for folks who pay attention to detail. The little mouse, for example, appears in a different spot on each page, and as the story progresses, the clock goes from 7:10 to 8:10. Even better, another hit storybook by Brown, The Runaway Bunny, is shown on a bookshelf in the room.

Reception to Goodnight Moon was mostly positive, but early sales were slow and the New York Public Library famously refused to stock the tale, deeming it too contemporary and sentimental. In fact, the book didn’t make it to the shelves of the venerable library system until 1973, nearly three decades after it was published. By then, sales had picked up considerably, with annual numbers increasing from 4,000 copies sold in 1955 to 20,000 copies sold in 1970. Its popularity continued to grow from there: As of 2017, more than 48 million copies had been sold worldwide. The book also appeared on the National Education Association’s list of Teachers’ Top 100 Books for Children, and was voted one of the School Library Journal’s Top 100 Picture Books in a 2012 poll. Even the New York Public Library eventually came around and included Brown’s classic story among its 100 Great Children’s Books From the Last 100 Years. Photo courtesy of Bookshop.org.

Harriet the Spy by Louise Fitzhugh

Harriet the Spy came out in 1964, in the midst of an American fascination with spies driven in part by the popularity of James Bond. Likewise, nannies were a hot topic on screen, with Mary Poppins and The Sound of Music taking movie theaters by storm. The two worlds didn’t often overlap — espionage and childcare aren’t the most natural pairing — but Louise Fitzhugh found a way to combine them in this quirky kid’s novel starring Harriet, an aspiring child spy and novelist, and her beloved, wise nanny Ole Golly. The book was a hit, and so was its main character, whom many critics hailed for her brilliance and precociousness.

Harriet the Spy came out in 1964, in the midst of an American fascination with spies driven in part by the popularity of James Bond. Likewise, nannies were a hot topic on screen, with Mary Poppins and The Sound of Music taking movie theaters by storm. The two worlds didn’t often overlap — espionage and childcare aren’t the most natural pairing — but Louise Fitzhugh found a way to combine them in this quirky kid’s novel starring Harriet, an aspiring child spy and novelist, and her beloved, wise nanny Ole Golly. The book was a hit, and so was its main character, whom many critics hailed for her brilliance and precociousness.

The praise was not universal, however. Some people thought Harriet could be a bit abrasive and disapproved of the book’s premise as it related to her spying on her classmates and other people in her life, and recording her opinions of them in the notebooks she carried with her. At one point in the novel, a notebook is taken from her in the schoolyard, and her peers read what Harriet wrote about them and shun her. In response, Harriet acts out — she bullies the kids in her class, talks back to her parents, and even skips school. For these reasons, among others, certain critics and educators viewed her as a bad influence, and the book was banned from a number of classrooms and libraries.

The controversies didn’t dampen the book’s legacy, though. Children loved, and still love, Harriet and her antics. Harriet the Spy clubs and costumes were tremendously popular in the 1960s and ‘70s, and a variety of film, television, and stage adaptations have been produced over the years, even as recently as 2020. The book itself was also included in a 2009 list of children’s classics by The Horn Book Magazine, and ranked at No. 49 on Time Out New York’s 2020 list of the best books for kids. Further, Harriet and her creator have served as an inspiration among queer women — Fitzhugh, who also crafted the beloved illustrations, was gay, political, an acclaimed fine artist, and a fixture in Manhattan’s downtown scene. She instilled a sense of progressive values in Harriet the Spy and across her other books. Photo courtesy of Bookshop.org.

The Snowy Day by Ezra Jack Keats

Ezra Jack Keats isn’t Black, but the protagonist of his most famous picture book is. The character’s name is Peter, and his story, The Snowy Day, is all about enjoying the first snowfall of the season in Brooklyn — making snow angels and a snowman, stashing a snowball in his pocket for later, and marveling at the wintry wonderland. It’s a delightful and universally relatable tale with vivid, mixed-media illustrations that won Keats the 1963 Caldecott Medal — one of the highest honors a picture book can receive. More recently, the New York Public Library named The Snowy Day one of its Books of the Century, as well as its most borrowed book of all time, with more than 485,000 checkouts as of early 2020.

Ezra Jack Keats isn’t Black, but the protagonist of his most famous picture book is. The character’s name is Peter, and his story, The Snowy Day, is all about enjoying the first snowfall of the season in Brooklyn — making snow angels and a snowman, stashing a snowball in his pocket for later, and marveling at the wintry wonderland. It’s a delightful and universally relatable tale with vivid, mixed-media illustrations that won Keats the 1963 Caldecott Medal — one of the highest honors a picture book can receive. More recently, the New York Public Library named The Snowy Day one of its Books of the Century, as well as its most borrowed book of all time, with more than 485,000 checkouts as of early 2020.

The book came out in 1962, at a time when few other picture books featured characters of color — especially characters that were not caricatures. Keats, who had worked as an illustrator on several published books by the time he wrote The Snowy Day, took note of this and decided to do something about it. . According to the executive director of the Ezra Jack Keats Foundation, which aims to promote Keats’ legacy as well as diversity in children’s literature, the author’s choice wasn’t political. He merely wanted to create a character that young, Black readers could relate to.

This wasn’t without controversy; some people didn’t think it was Keats’ place, as a white, Jewish man, to depict the experience of an African American child. But for others — including educators, activists, parents, and kids — it was inspiring. Keats received countless letters of support and appreciation in the years following the book’s publication. And Peter and his orange-red snowsuit remain a cultural touchstone. The character recurred in several of Keats’ later books, and a 50th anniversary reprint of The Snowy Day in 2012 featured the Life magazine photos of the child who inspired Peter, as well as a letter by none other than Langston Hughes. Photo courtesy of Bookshop.org.

The Phantom Tollbooth by Norton Juster

Norton Juster famously wrote his classic children’s novel The Phantom Tollbooth while avoiding the work he was supposed to be doing on another book. After three years in the Navy, Juster returned to New York to work as an architect and write a book for children about cities and city planning. He received a grant for the project, but the research bogged him down and brought him back to his childhood — a period he describes as one of confusion and disconnection. He ended up writing about that childhood, and that child, and the story became The Phantom Tollbooth.

Norton Juster famously wrote his classic children’s novel The Phantom Tollbooth while avoiding the work he was supposed to be doing on another book. After three years in the Navy, Juster returned to New York to work as an architect and write a book for children about cities and city planning. He received a grant for the project, but the research bogged him down and brought him back to his childhood — a period he describes as one of confusion and disconnection. He ended up writing about that childhood, and that child, and the story became The Phantom Tollbooth.

Released in 1961, the book centers around a boy named Milo, who receives a package containing a highway tollbooth that allows him to journey to a fantastical place called Lands Beyond, where he rescues princesses, explores foreign landscapes, and just generally escapes from his dull, everyday life. The story provided a similar sense of escapism for its readers — but not everyone thought that was a good thing. According to Juster, many people believed children should not be fed stories that weren’t grounded in reality. Others wondered if children were even the intended audience — the book contained ironies, sophisticated language, subtle allusions, puns, and a deluge of verbal and linguistic gags.

After a slow start, the book became more and more popular. Kids leaned into the rhythms of its joyful language and — whether they knew it or not — experienced just how satisfying learning could be. Juster received countless letters from fans of all ages over the years, as his quirky story was translated into multiple languages and adapted into a film, a stage play, an opera, and a symphony. In 2011, two new versions of the book hit shelves: an annotated copy with drafts and notes by both Juster and illustrator Jules Feiffer, and a 50th-anniversary edition that included tributes by Maurice Sendak, Philip Pullman, and Michael Chabon. The book was also listed among teachers’ favorites in a National Education Association roundup, and voted one of the Top 100 Children’s Novels in a School Library Journal poll. Photo courtesy of Bookshop.org.

Strega Nona by Tomie DiPaola

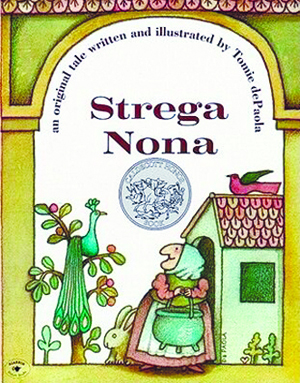

Published in 1975, Tomie DiPaola’s Strega Nona centers on a kindly Calabrian witch whom townspeople visit for matchmaking, headache cures, and wart removal. It’s a charming story with whimsical illustrations, and it quickly became a hit with both kids and educators upon its release. It even won a 1976 Caldecott Honor — the distinction given to runners-up of the Caldecott Medal — and was among the New York Public Library’s 2013 list of 100 Great Children’s Books From the Last 100 Years. Since the late 1970s, the book has also spawned a series of offshoots and sequels featuring the main characters — Strega Nona, of course, and Big Anthony, who helps her out around the house.

Published in 1975, Tomie DiPaola’s Strega Nona centers on a kindly Calabrian witch whom townspeople visit for matchmaking, headache cures, and wart removal. It’s a charming story with whimsical illustrations, and it quickly became a hit with both kids and educators upon its release. It even won a 1976 Caldecott Honor — the distinction given to runners-up of the Caldecott Medal — and was among the New York Public Library’s 2013 list of 100 Great Children’s Books From the Last 100 Years. Since the late 1970s, the book has also spawned a series of offshoots and sequels featuring the main characters — Strega Nona, of course, and Big Anthony, who helps her out around the house.

Despite its accolades and popularity, however, Strega Nona was widely banned in American schools and libraries. Like other books that celebrate magic and the supernatural — such as the Harry Potter series and A Wrinkle in Time — the story was controversial for its positive depiction of witchcraft. Strega Nona is a witch, after all, and a well-liked one at that: Her magic pasta pot conjures delicious meals with one of her spells, and even the local priests and nuns visit when they need cures for their various ailments.

Interestingly, many people initially believed the book was a retelling of an old Italian folktale. It certainly reads like one: After Big Anthony attempts to use magic in his boss’ absence, a massive pasta explosion ensues and Anthony learns a valuable lesson about respecting Strega Nona’s magic and cleaning up his own messes. But while the story does contain some popular themes, its premise is purely a work of DiPaola’s vivid imagination. The source of the confusion can be traced to some very early printings of the book that dubbed Strega Nona “an old tale retold and illustrated by Tomie dePaola.” Newer versions attempt to clear this up, calling it an “an original tale written and illustrated by Tomie dePaola. Featured image credit: Pixabay/ Pexels

Facebook Comments